georgiaroad

Chairman

Purveryor of all things of the prototype freelance GEORGIA ROAD

Posts: 250

|

Post by georgiaroad on May 5, 2012 23:59:46 GMT -5

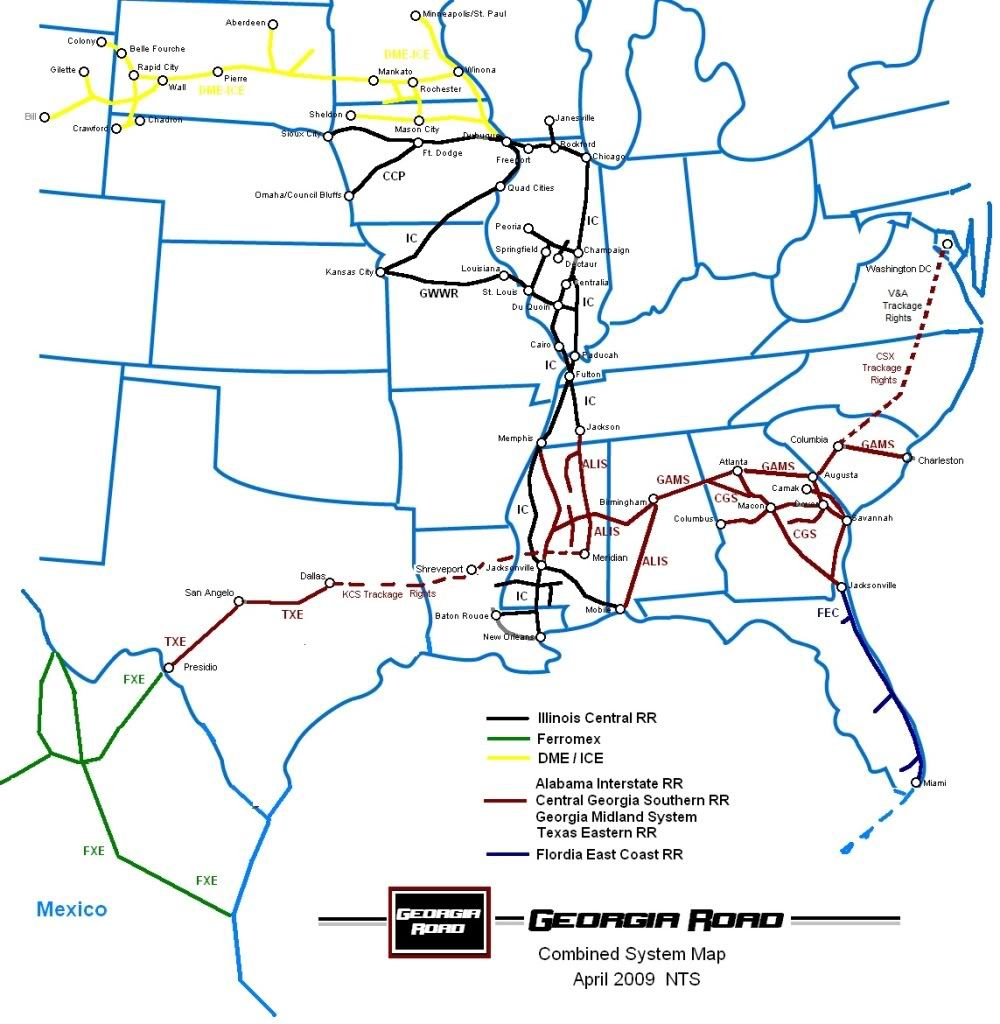

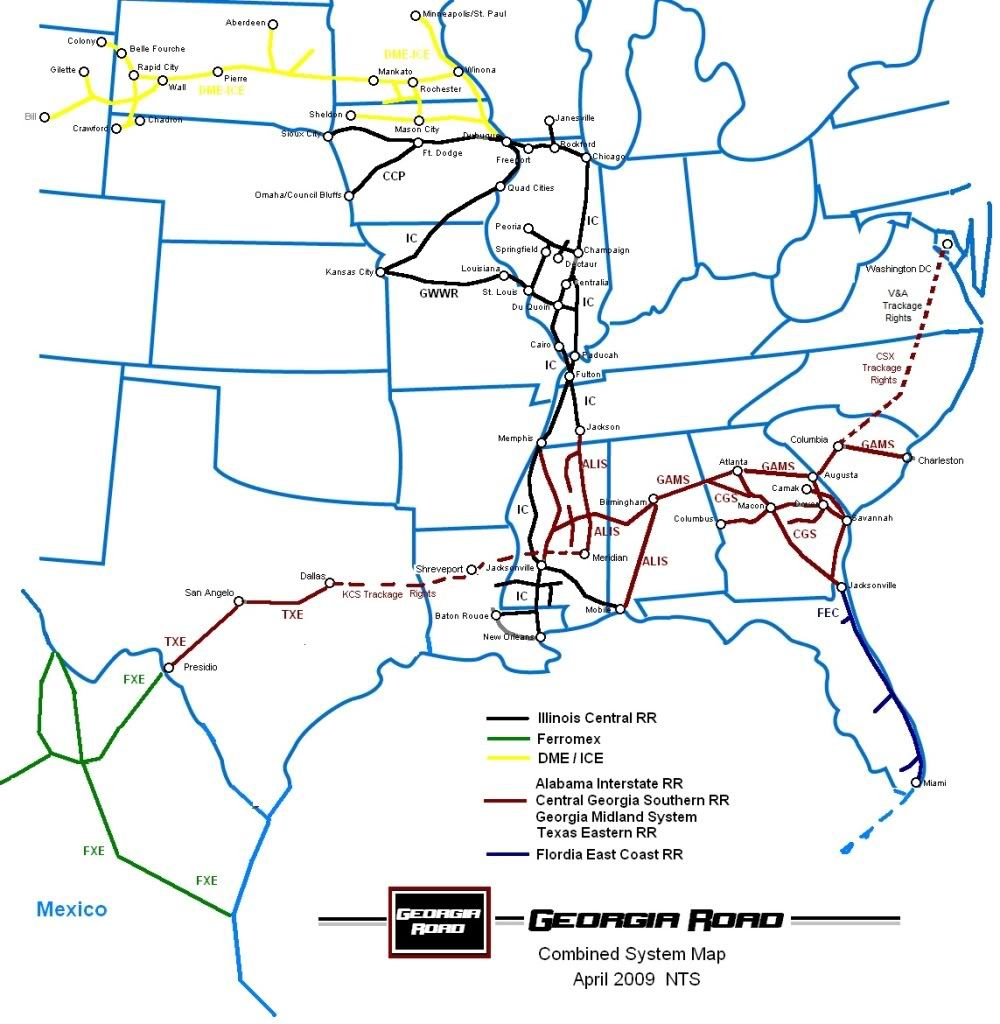

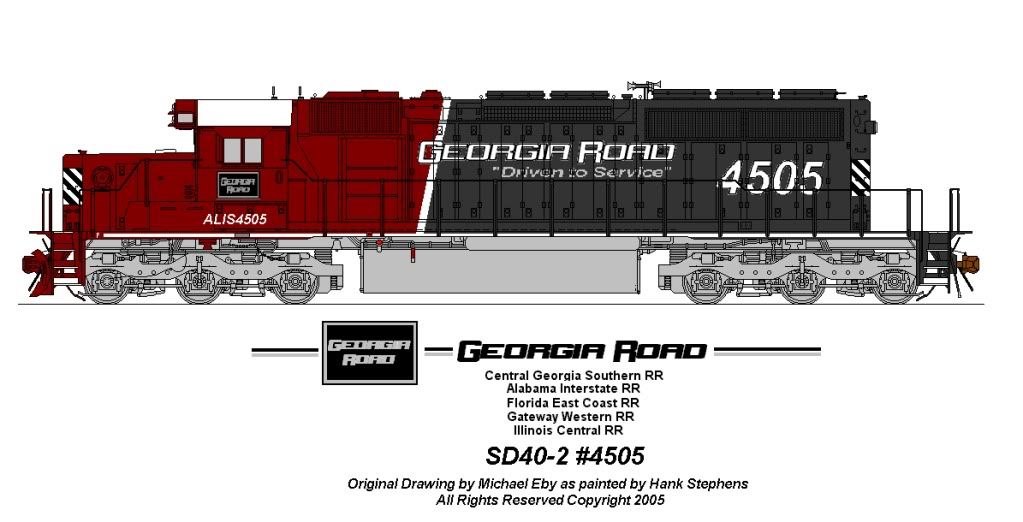

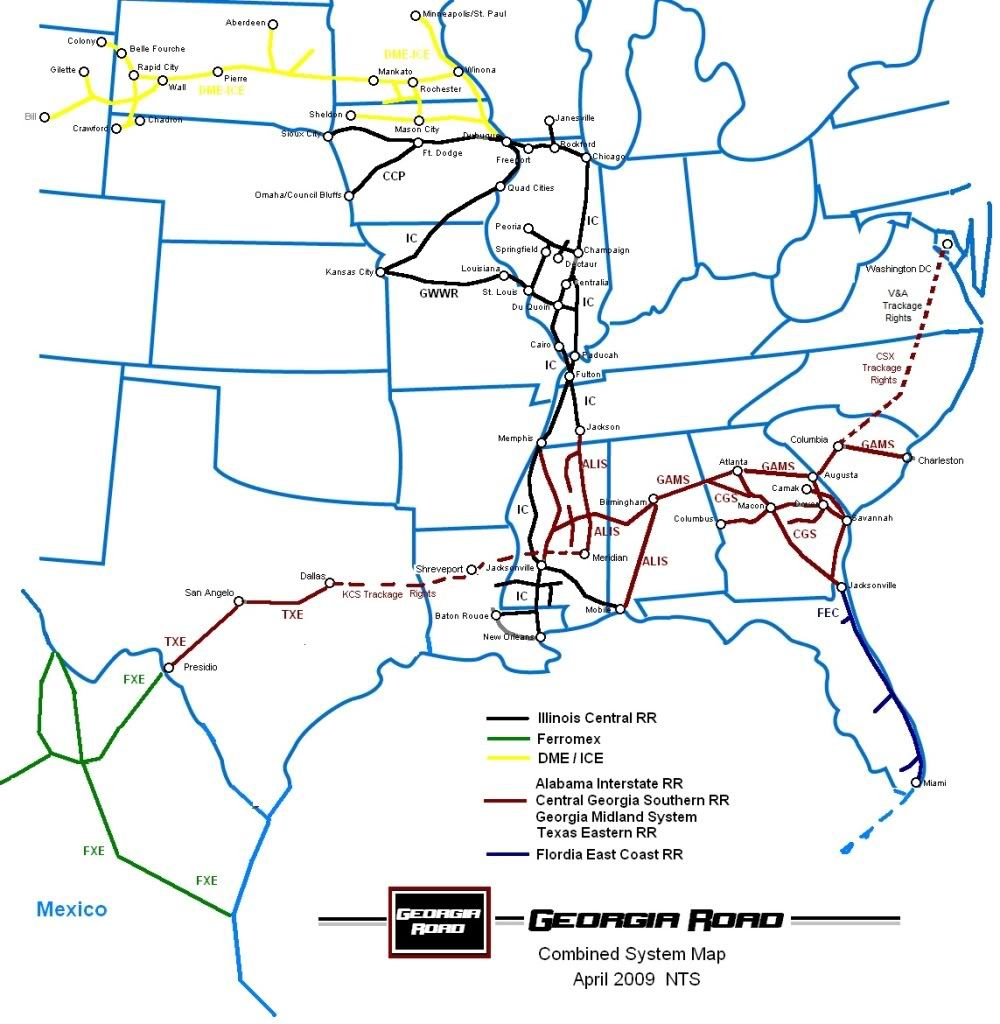

With a pretty good understanding of the two sides of the triangle that defines my concept, I figured I would spend a few minutes on the larger and primary focus of my prototype freelancing in the form of the Georgia Road. This is a modern Class One that has made some very strategic purchases over the years since its original spin-off in the 1980s from NS. The Georgia Road formed out of the ashes of the Central Alabama & Southern RR (CA&S). This regional manged to build an empire on secondary mains and branches running what at the time was the infancy of double stack intermodal traffic, primarily for early proponent American Presidential Lines (APL). Like the NYSW in the northeast, CA&S proved it could run circles around the class ones in the Southeast, due to its lean management, non union labor and innovative operations. The downside is that it was highly leveraged and its management became greedy to the point of stealing the company and reducing it to a shell. By the early 1990s, the CA&S was bankrupt and the Georgia Road purchased the estate from a trustee and began to build the current day system. The intermodal traffic was still bread and butter for the new railroad, but the rise of Powder River Coal being burned in the Deep South gave a huge revenue stream not present in the CA&S predecessor. It added the FEC to reach Florida, and expanded operations toward Memphis via ex GMSR-MidSouth-KCS purchases. The regional captured the IC from CN, placing it firmly as a Class One railroad. The Gateway Western RR followed to give it a run from Kansas City to Florida, a major increase in rates as coal shipments now traveled even more miles on Georgia Road rails. The next purchase brought the Georgia Midland RR regional into the fold. This gave the Georgia Road a link through Atlanta into South Carolina, where it established the Dominion Gateway as far north as Washington DC for its intermodal. Next it purchased interest in Ferromex, following the KCS-TFM example of how to capitalize on NAFTA traffic. After using trackage rights on UP and later KCS, the Georgia Road pruchased trackage out Dallas that linked the Ferromex through its Texas Eastern Rr (TXE)-Fort Worth and Western RR (FWWR). While such reaches seemed rather long and tenuous, the idea was to give its QuickSilver Intermodal Service deeper access into produce and express markets form the growing regions of Mexico and Texas the Southwest. The DME-ICE merger came next, giving Georgia Road a link into the Powder River Basin. Now Georgia Road could finish the third way in and run its coal trains to Deep South Generators without UP or BNSF. The Georgia Road finds its core between Memphis and Atlanta, over what is known as the Alabama Interstate RR (ALIS). Like the Family Lines System or the original Southern RR, the Georgia Road operated separate railroads under a common holding company, with semi autonomous day to day operations under a common paint scheme. Here is the current system map:  |

|

georgiaroad

Chairman

Purveryor of all things of the prototype freelance GEORGIA ROAD

Posts: 250

|

Post by georgiaroad on May 8, 2012 1:04:47 GMT -5

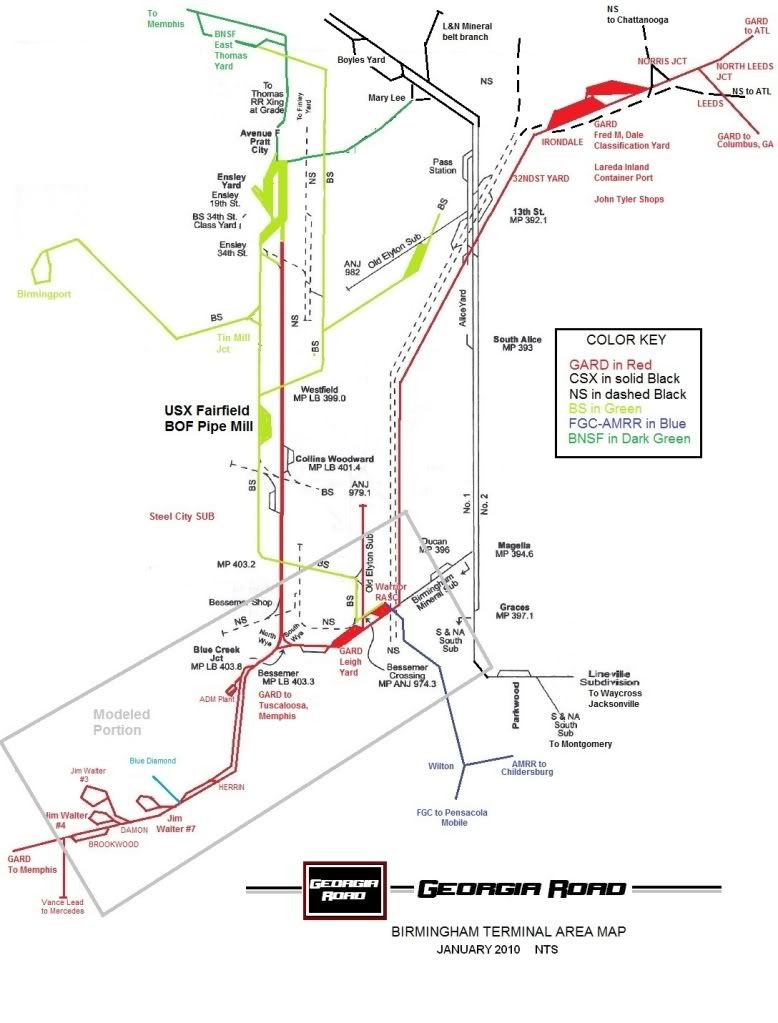

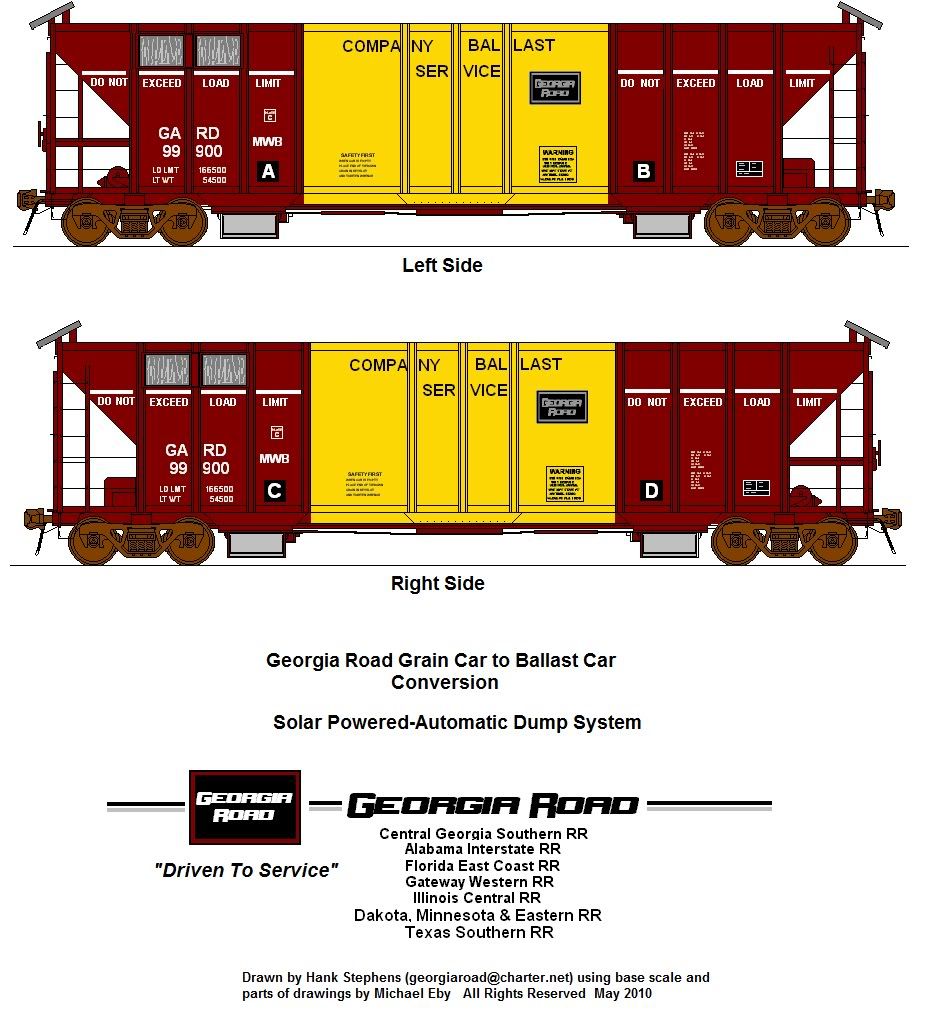

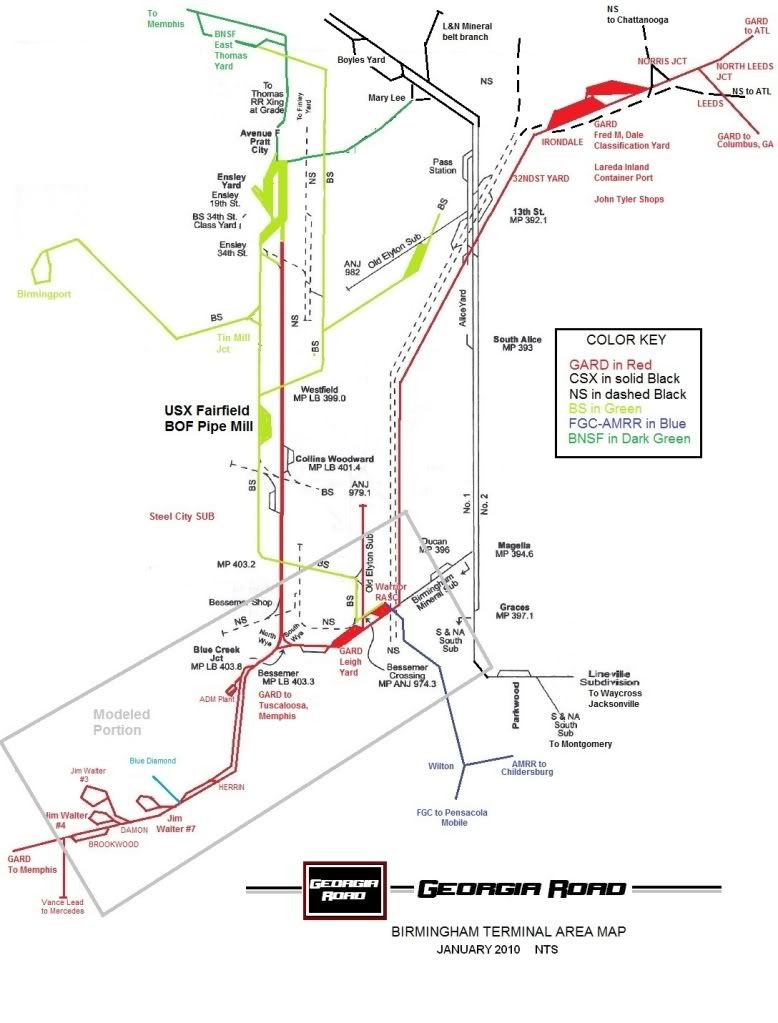

I can tell anyone who is committed to building a protofreelance railroad to be ready for hours of decaling and painting. I have collected way too many kits and projects over the years. My bench looks like a bone yard with spiders patroling the cobwebs for anything that might be attracted to the light that burns over it all the time in the garage. Keeping the door closed helps, but it still gets dusty and nasty. You cannot even image what some of these projects looked like when I started. Designing a concept is easy. Unless it is a one or two horse railroad, a modeler will find a lot of tedious hours of building and lettering ahead. To date, I have done about two dozen Georgia Road and FGC cars, mostly woodchip and various boxcars. Many were basket cases I got off Ebay in lots as forlorn kits or with damaged or missing parts. the Stephens Railcar side has ressurected most of them. I have to say, getting an old LBF paperbox with bad paint, missing ladders and those horrible trucks and weight, then running it through a scale rebuild with Atlas trucks, Kadee #5 couplers, my own odd weighting technique which involves gorilla glue and 16D finish nails and replacement parts is a feat. When the paint goes on you think you have done something, until you realize that each car will take 2-4 hours of decaling to complete it. I dread painting and like decaling, but I found out I can paint a whole lot more than I can finish in a reasonable time. My better half gets tired of these cars sitting around, asking when the next train will take them out of the house and out of storage on the entertainment center (seven more were set out today for pickup--the fruit of three weeks work between all my other cares of life). I found my collecting quickly overrides my concept. As a result, I decided to start drilling down my concept to the actual layout. My modeling is focusing on a train at the time. The Georgia Road Interstate Division in HO Scale is a double deck, around the walls. the focus is the section of mainline linking the Memphis Gateway into Birmingham. The actual model is even more specific, running from just north of Tuscaloosa to Bessemer in the Alabama Blue Creek Coal belt. The plan will feature two modern balloon loadouts and a strip mine loader. One loop is the Jim Walter Six Mile Railroad that runs from the Six Mile Mine to the Georgia Road mainline at Brookwood, a modeled marshalling yard and helper point. This line is a combo of the former GM&O and L&N and exists today as the Alabama Southern RR and CSX Brookwood/Blue Creek Sub. The real Walter Energy is opening a new field in 2014 right near where I placed the fictional Six Mile operation. It is about six miles from the NS main. I just found that out in a press release. In my world, the Sic Mile takes Georgia Road unit trains and hauls them up the steep Six Mile branch to load using its own power. Trains are then assembled by Georgia Road at Brookwood and head north to Birmingham, where they will turn South for the port of Mobile or head east for one of several Southern Generating plants. With Japan switching off its nuclear power, the export coal business will sky rocket. Six Mile also runs its own train to the coke plants in Tarrant City that are also owned by Walther Energy. Think of the Onieda & Western or SECX coal trains working on the L&N back in the 80s. That is my inspiration. All this coal action is backdropped by the main line trains linking the original Georgia Road with its IC side. I figure a couple of intemodals, three manifests and several Powder River Coal trains running thorugh as they currently do no NS to the north. Since Georgia Road has its own link to PRB, these trains will now be a usual site on the Interstate main. Due to grades, as swing helper has to help the DPU coal trains over the gap in the mountain into Birmingham. the mainifests get a shove too, and the QuickSilver Intermodals use rear DPU. Sections are double track or single track with long and close sidings. Merciedes Benz has a plant in Vance, AL, about ten miles south of the Georgia Road main at Brookwood. NS serves it for real, but adding a branch is not hard or long, and the autorack traffic adds another interesting kink. Since I work at KIA in West Point, GA, I get to see how these new foriegn automakers work. The footprint is very small cmpared to the Rust Belt of the Great Lakes region. It is containers in, and autoracks out. Suppliers are grouped around the assembly plant, and a few get plastic pellets for injection moulding or coil steel for stamping and processing parts. KIA stamps its own frames, so it gets coil at an onside transfer plant where trucks move it to the stamping building or down the road to suppliers. the workhorse of the line is the L26 job that runs out of the Bessemer Terminal in greater Birmingham. Georgia Raod maintains a large classification yard and intermodal ramp on the east side of town. It is not part of the model, but is represented by several daily transfers that got between the Class Ones and the Bessemer Terminal, known as Leigh Yard. The big yard was too congested, and the Mercedes operation needed a terminal to work its containers closer to Vance. Lareda went from a local point serving west Birmingham industry to a sattelite intermodal ramp and auto mixing facility. The L26 local runs south out of here every day, working all the non-coal industry as a turn that gets just south of Brookwood at Herrin, AL, site of a Georgia Pacific log loadout. There is a chip mill at Brookwood, a couple of Mercedes suppliers (one injection moulding and one coil blanking operation) and an OSB mill too that gets in glue and ships boxcars full of OSB panels. The L26 job covers about a hundred mile round trip each day, not much except for all the traffic that it runs against that makes it a siding queen when not working the sidings at Brookwood where double track gives the local a reprieve from dodging main line trains. There is a larger Blue Circle Cement Mill in Bessember, a rather larger Bio energy transload yard and a pipe coating mill, all in the yard limits of Leigh Yard. You can run over to the "Bessemer Bullpin" and see the latest Stephens Railcar TGX rebuild being tested or resting between shakedown runs. Stephens Railcar acts as the main Georgia Road contract backshop. They have a rather large facility inside the classification yard on the east end, but due to space limitations, dynamic testing and tweaking was moved to the Georgia Road running repair shop at Leigh Yard. Power for the Mercedes container and autorack trains is maintained here, along with power for the local yard jobs, plant switchers and L26. While the Six Mile RR power has its own service facility at the Brookwood Junction, the power for the "coke coal" turns gets fueled and inspected here on the mainline fuel pad, just to the west of the bullpin service area sandwiched between the service lead and the remote control yard lead. I am a former NS trackman with a little experience in MofW gangs. I have a full CAT-09 tamper gang that shows up from time to time, just to make things interesting. Add to it the heat inspection high rail trips, spot welding, and even rail griding with what is basically a disquised track cleaner and you have a typical run down on the layout. The OCS train show up too. Think ATSF El Cap train. Georgia Road likes the high-level cars and has built a rather impressiive business train fleet pulled by FP45s. Georgia Road lets Stephens Railcar run the TGX rebuilds along with the test car at times during the week also. The coal trains to and from Brookwood to Mobile make a good contained move to test the latest and greatest TGX rebuild. Well, as usual, I got long-winded. I hope this gives someone some ideas. This is twenty years of concept planning. Everything I mentioned is basd on an actual NS or CSX operation, or something close. I just change the names and routes to protect the innocent. My modeling focuses on each train on the layout. Right now, the chip cars and boxcars are to populate the L26 local. Much of that comes from or is heading to the FGC-AMRR connection at the Birmingham Southern RR Ensley Yard, loosely represented. I am posting a terminal diagram that highlight this info. This is actually a map from a Birmingham Termical Timetable for CSX, circa 1990s. I did not add any new track, only embellished some of the existing stuff and added my yard locations. The Georgia Road is a conglomeration of CSX and NS track. Some is secondary, some abandoned or shortlined and some as it is in reality. The trick to a good proto freelance concept is to draw you in and be so seamless from fact to fiction that you have a hard time separating the two. Some would say freelancing is a cheat for modelers who cannot do prototype modeling. Freelancing on its own is much easier than when you stick the prototype in front of it. These places are real, though in my concept they may not be exactly the same. Still you can go stand in the middle of Brookwood. You can see the Jim Walter mines--you just will not see high ballasted mainline with a constant parade of trains. Go south to the NS Birmingham-Meridian AGS main, and you will see the Georgia Road, or at least the feel of it.  |

|

georgiaroad

Chairman

Purveryor of all things of the prototype freelance GEORGIA ROAD

Posts: 250

|

Post by georgiaroad on May 8, 2012 6:40:55 GMT -5

I have read that story with great interest. It does a good job of seaming the real with the fictional. Feel free to include the Georgia Road.

I have one too. I will post it below WARNING--VERY LONG TOILET READING

Old Dogs and New Tricks:

The Story of the Georgia Road

and the

Alabama Midland

Heat demons danced lazily along the blacktop highway linking the smaller sleepy town of Smith’s Station, AL to its larger neighbors of Phenix City, AL and Columbus, GA to the east. It was a typical late summer afternoon in the heart of the Chattahoochee River Valley, gripped in the remains of an unusually late heat wave. The poplar trees grouping between stands of southern pines were already announcing relief from the heat in the form of cooler Fall weather. Their summer worn green leaves were tattered and showing signs of turning into the yellows of Fall. The cicadas chirped incessantly, and gnats danced in the swirl of momentary breezes in the overgrowth between the road and the tracks.

The town of Smith’s Station gained its name from the local Central of Georgia depot that once perched at the west end of a long sidetrack. This namesake building was now only a memory to older folk in the area and the location was marked only by a grassy knoll in front of a grocery store strip mall next to the mainline. It, like many depots and rail lines of its era and location, were now gone, victims to the economies of scale brought about by the large rail corporations formed during the mergers of the 1980s. The town even lost its full name, as younger residents called it Smiths, deleting the “Station” from the name in the same way the large rail corporation had abruptly removed the physical structure so many years before.

Downtown Smith’s Station consisted of the main road paralleling the tracks intersected by several cross streets around the old depot location, which marked town center. Along with several connected storefronts, a newly constructed convenience store and the grocery store strip mall huddled around the former depot site and the streets that congregated around it The twin rails of the Columbus, GA to Birmingham, AL main line sliced through the heart of this montage, unremarkable now save the long pass track that still kept the name Smith’s Station on the railroad map.

The wail of a three chime Nathan horn suddenly interrupted the sleepy repose of the town, drifting in on the stirring breeze. A locomotive headlight rounded a distant curve, its beam wavering in the heat radiated from the neat granite ballasted track. Again the horn sounded as it continued the two-longs one-short one-long warning, announcing the train’s soon arrival at the main crossing. Immediately, the crossing gates awoke in the midst of ringing bells and flashing lights. The crossing gates arced downward from their vertical watch to horizontal warning of the approaching train. The rails began to creak and scream wildly, stressed beneath the weight of the fast moving train. This noise was soon drowned out by the rumble of EMD primemovers as the train glided with horns blaring through the crossing.

While one may have expected the black and white of Norfolk Southern or the blue-gray-yellow of CSX Transportation, the trio of locomotives charging the train over the crossing carried a new but unfamiliar rich burgundy and weathered black scheme. Their wide nose cabs were streaked with black and white barricade stripes wrapping around and ending at the cab sides. On their long flanks, black outlines highlighted the white words “Georgia Road”, which juxtaposed between the white diagonal stripe separating the burgundy from the black on the long hoods. The lead unit was a SD75M, a fourth generation rebuild product of a GMLD built SD60 for The Georgia Road. The second unit was a cab-less SD-40M-3 followed by a GP60M trailing, both painted and marked similar to the lead unit. Their flanks bore a logo and the words “APC Contract”. As the exhaust fumes and engine noise faded, the rhythmic tapping of turned steel wheels rolling over the nearby switch frog permeated the scene. A seemingly endless string of both NSC and Gunderson 53’ loaded double-stack well cars followed the locomotives, painted in blacks, blues, yellows and reds. Names such as APC, Pacer Stacktrain, and Trailer Train could be seen on their sides as they streaked through the crossing. The words “Eagle Flyer Service” were neatly lettered on the black cars, which carried the Georgia Road reporting marks of GARD. Town was now cut in half, separated by over a mile of fully loaded double-stack freight cars hustling through the crossing.

A resounding boom of slack bunching rippled through the speeding cars, hinting that the engineer had set the train into dynamic braking mode for the slide down into the Chattahoochee River Basin. With no warning, the final car zipped past the crossing and down the tracks, a winking FRED marking the end of the train. The crossing gates just as quickly arced back up, returning to their silent vertical vigil. In seconds the last car and the FRED disappeared around a distant bend as the few cars that waited for the train crossed the tracks and accelerated to their destinations.

Few industry analysts or sideline railfans could foresee the significance of the Illinois Central Gulf Railroad (ICG) spin-off of the 403 miles of its east-west Louisiana and Mississippi Divisions stretching from Shreveport, LA to Meridian, MS on March 31, 1986 to Midsouth Rail Corporation. It was hailed by most as a dying railroad trying to re-capitalize itself by divestiture of what would figure to be about half of its pre-1986 route mileage. Most expected the ICG would quickly follow the footsteps of the Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railroad (the Rock Island, as it was known), or the Penn Central Railroad. Both of these rail giants collapsed from a combination of years of deferred maintenance, a deep recession of the mid 1970s, and an eroded traffic base lost to owner-operator trucking running the US Interstate System. Tightly held federal control of railroad rate structure left no room for rail transportation to maintain profitability. There were just too many railroads, too few customers and little hope for the industry in general.

The ICG garage sale kicked off by the Midsouth transaction proved the harbinger of a new era in modern railroading known as the regional spin-off craze of the late 1980s and 1990s. Following at the heels of ICG, many Class One operations found they could actually attain profitability in a deregulated environment where unprofitable lines could be handed off to local interests and removed from their bottom line. These local operations possessed low overhead and a determination to make these questionable lines work. The class one railroads simply needed to pick up and deliver the traffic from these new regional and branchline operations, gaining a cut of the revenue without the expense of maintaining it. The old adage of “you can’t teach an old dog new tricks,” seemed completely misguided in this new world of rail transportation, as regional and local railroad interests breathed new life and viability into the old dog branch lines deemed nothing but liabilities on the Class One balance sheets.

Georgia Road Transportation (called simply “The Georgia Road”) inherited the legacy created by the ICG spin-offs at its inception on August 31, 1996. This legacy was no longer surrounded by a climate of overly optimistic euphoria produced by the radical visions of success held by the regional railroads spawned from the ICG. Serious problems created by the very public and damaging collapse of several of highly touted regionals such as the Chicago, Missouri and Western RR and Chicago Central brought to light the immense problems faced by the highly leveraged new railroads, whose infrastructure suffered from years of deferred maintenance and an eroded traffic base. Georgia Road was aptly born to run hard and fast against the norms of railroading at the time. The climate of railroading in the mid 1990s proved a trial by fire with residual profitability the only guarantee for ultimate survival. Not only did Georgia Road have to run, but it had to run profitably and efficiently into unexplored markets in its realm. The old dog lines it inherited had to learn many new tricks, with mastery an immediate requirement just for short term survival.

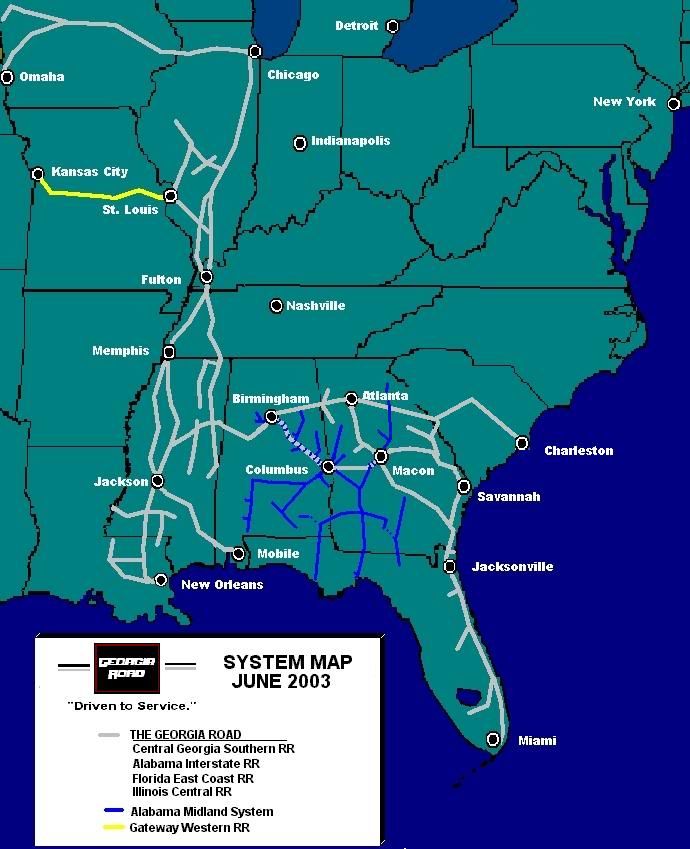

Georgia Road found its roots deeper than its actual start of operations in 1996. It was the inheritor of much of the former Central Alabama & Southern Railroad (CA&S), a predecessor road known for its “out of the box” approach to railroading and one of the 1980’s regional spin-off darlings of the financial world. CA&S was born on June 9, 1990 after a group of shippers, politicians and investors calling themselves the Alane Group approached Norfolk Southern Railroad (NS) about the possibility of purchasing a then unnamed section of trackage in the Southeast. NS made known that it was interested in divesting some of its Southern region secondary and branch lines. In fact, it had only recently leased shortline operator Railtex a section of line between Smithville, GA and Eufala, AL under the name of the Georgia & Alabama Railroad (GAAB). The Alane Group had grander ideas, and more money to commit. This meeting was not by chance, but followed a very large divesture to Wheeling and Lake Erie RR (WLE) in Pennsylvania, creating the first NS spin-off regional of any measurable size. NS continued negotiations through 1989 with the Group with little pretension as to where, how much and when a sale might take place.

In December of 1989, NS announced that it was selling its entire former Central of Georgia trackage (now part of its Georgia Division) to Alane Group at an undisclosed price. Insiders did not seem surprised, as NS had downgraded all of the lines in an effort to control the more costly requirements of the Central of Georgia work rules inherited when it gained the Central of Georgia under its former name Southern Railway in the early 1970s. NS could effectively eliminate the costs, without losing the on-line traffic as NS retained control of traditional gateways in Atlanta and Birmingham. The purchased trackage stretched from Savannah, GA through Macon and Columbus, GA all the way to Birmingham, AL. Also included were several branches including the lines radiating out of Columbus and Albany, GA. Another line ran north from Macon to Atlanta, GA through Griffin. The Alane Group would act as a local representative to NS, funneling all traffic to Macon and Birmingham terminals. The new road was limited in that it could not compete directly with NS in existing overhead traffic, nor was it allowed to directly reach BN at Birmingham, AL for fear that BN would grab the new road as direct access into the Southeast rather than using historical NS links.

The Alane Group quickly moved to start its railroad the following June in 1990, under the name Central Alabama & Southern RR (CA&S). The new management quickly proved adept at running a railroad, resurrecting regional piggyback service into the major cities served by the CA&S. In late 1990, CA&S stunned NS when it announced an operational agreement with Midsouth and Union Pacific hauling overhead double-stack trains into Atlanta and Savannah. NS balked, but since the traffic was not existent at the CA&S start-up, their objections fell on legal deaf ears. American Presidential Lines (APL) came onboard as the primary customer and CA&S contract stack trains began linking up with Midsouth at Meridian via the newly acquired Meridian and Bigbee RR(MB). Midsouth then handed off the trains to UP in Shreveport, LA.

CA&S began an ambitious upgrade program in 1992 as it completely reworked much of the former MB and access to it via its former CSX Transportation Montgomery-Selma, AL line. This link from Meridian followed a branch into Columbus, GA from Montgomery. At Columbus, the newly upgraded route connected to the former CofGA main into Macon, GA where trains could continue north or west on the heart of the CA&S to Atlanta and Savannah. APL stack trains grew in size and frequency as APL quickly established a “Southern Gateway” for its land-bridge traffic. This premium service coupled with strong domestic intermodal, coal contracts with several on-line Southern Company power plants and paper traffic propelled the CA&S to the forefront of the regional scene in late 1993. Wall Street even hailed the CA&S as the “rogue railroad with its hand on the pulse of the future.” CA&S developed a reputation as a sure investment, posting returns doubling the industry standard during 1993.

The CA&S locomotive fleet changed as quickly as the railroad’s profitability. At start-up, the roster included a grand helping of former NS high-hood units, ranging from ALCO trucked GP-35s and GP-30s, to SD24, SD35 and SD45 model units. It quickly purchased many of the former Milwaukee Road (MILW) SD40-2 s from EMD and completely rebuilt them. Former NS SD40 and SD40-2s soon followed as their leases expired on NS. Conrail (CR) cast-offs in the form of GP-38s and GP-40s came in 1993. More SD-45 units came in 1994, this time from CN&W, giving the CA&S the distinction of owning the only non dynamic equipped SD-45s built. As SP thinned its roster of first generation units and switchers, CA&S added to its branch line and yard assignments switcher models such as SW-1500s, GP-9Es, SD-9Es and GP-20Es. Second hand units were completely overhauled, and became the backbone of the growing regional.

To keep its roster running efficiently, CA&S contracted Stephens Railcar out of Montgomery, AL to head purchasing, rebuilding and maintenance of its fleet. Stephens Railcar worked feverishly to rebuild the dozens of worn out units acquired by CA&S, turning out modernized and practically new power to meet the railroad’s endless motive power shortage. Stephens Railcar quickly expanded its operation in Montgomery to the old WofA car shops, restoring the historic complex as a modern working landmark determined to meet the CA&S demand for rebuilt power.

CA&S expanded again in January 1995, purchasing more ex-NS and CSX trackage, giving it direct access to the ports of Jacksonville FL and Charleston, SC. Stack train frequency and number moving over the CA&S increased several times over, as CA&S proved it could move these trains over its lines and bypass many of the traditional gateway choke points. With so

much success in a growing intermodal service, CA&S revenues climbed as did the euphoria that success seemed inherent. In another of its many off-the-wall maneuvers, CA&S purchased the Charleston Naval Yard after government downsizing of the military closed it in 1994. Convinced it could capture and double its share of lucrative land-bridge double stack traffic, CA&S sunk millions into the project, completing the first phase of a project it called Sea-Path.

Sea-Path was the culmination of CA&S dreams of becoming the premier carrier for much of the land-bridge traffic in the U.S. The idea called for the former Charleston Naval Yard to be rebuilt into a deep-water container port in two phases. Phase One opened the port and four piers. Phase Two looked at the construction of a modern railcar sort yard and opening of the final six slips. The project in its entirety would be the eastern version of the Long Beach, CA seaport facility, completely state of the art in design and operation. In the opinion of CA&S and its backers, one simply had to build the site and shippers would come in huge numbers as CA&S, Midsouth and UP shuttled multitudes of intermodal and doublestacks between the West Coast and Charleston.

At the power desk, CA&S realized it could no longer support the tight scheduling of its fast stack trains with secondhand and rebuilt power. In September of that year the railroad took delivery of two orders of GP-60M and GP-60B units. Orders for SD-60s soon followed as CA&S announced its Fleet 2000 project aimed at modernizing its core fleet to a minimum Dash-Two standing by the year 2000. Stephens Railcar, now the CA&S defacto heavy shops and service provider, was charged with upgrading the best of the non-Dash-Two locomotive fleet or replacing them unit by unit. The rebuilder had left its small Montgomery operations for a brand new, state of the art facility near Birmingham, AL for locomotives and a brand new car shop in the hamlet of Dadeville, A to the south of Birmingham. AL.

Troubled waters began to stir for the railroad that could do no wrong as the 1990s wore on into the last half of the decade. A costly derailment and hazmat spill of a collision between an APL stack train and chemical laden manifest near Fort Valley, GA in November 1996 marked the shape of things to come. FRA investigations revealed gross violations in maintenance and engineering. The findings were so severe that an investigation was put in place to evaluate the whole railroad. Gross negligence was found not only at the wreck site but all over the system. The massive upgrades of the early 1990s had not been maintained, and in most cases nothing but patch repairs were implemented system-wide in following years. The railroad has pulled its capital budget to kite its stock prices, and to support the construction of the Sea-Path facility. APL, the largest single customer balked, fearing the loss was not a freak mishap but a chronic problem about to reach a critical mass. FRA internal investigators uncovered a slow trend toward increasing delays and damage due to bad track and road failures of power. The CA&S had been incredibly lucky using improper reporting techniques or blatant cover ups to keep the true shape of its plant and structure in the shadows. but the constant pounding of the trains on poorly maintained track was finally taking its full toll. FRA officials also found little or no hard evidence of capital expenditures to correct maintenance problems.

Derailments were on the increase and CA&S management turned a deaf ear, choosing to cover up rather than address growing concerns. They continued diverted greater amounts of monthly income at staying the railroad’s historically higher than normal stock price, instead of correcting the mounting problems. Only stop-gap efforts were in place as CA&S covered losses with interim lease power and paid increasing service penalties due to slow unraveling of its scheduling. Creative accounting and public relations spin kept the stockholders from knowing the true nature of the growing disaster that lay just out of sight.

The financial position of the company fell considerably during the second quarter of 1996. The Sea-Path project was floundering badly as only one shipper, Evergreen Container Lines, signed on to use the facility. Evergreen was not a stranger to the area, simply moving its cramped operation across the bay from the Port of Charleston to the Sea-Path facility where it had room to operate. With no real income to offset the cost of the Sea-Path project and plagued by constant cost overruns,. CA&S pulled money from it railroad operations again and again to pay interest and payments on money borrowed to build the Sea-Path project and the original railroad purchase from NS. The result was that CA&S quietly gutted it capital improvement program in late 1996, dismantling its maintenance and engineering in an effort to slash costs to keep cash flow available to meet loan interest payments. Cash flow for day to day railroad operations eventually dried up completely. SRCS continued it its role as the principal back shop, but it too sensed the CA&S was in trouble. SRCS always worked for CA&S on a speculative basis, and for the first time money owed was not being paid in a timely manner. As a result, CA&S found it could no longer support its Fleet 2000 initiative, instead relying on stop gap short term leasing of less than stellar locomotives and railcar fleets, all of which added to the constant problem of bad track.

On Saturday, September 1, 1996 the CA&S came to a literal standstill as it defaulted on every one of its loans, including the principal loan that financed the purchase of the railroad from NS. Customers and employees alike found the doors of agencies and offices locked and the phones unanswered. Creditors immediately seized all fluid assets and filed multiple lawsuits in an effort to recover lost principle and interest. Shippers flooded various state DOT offices and Federal departments howling over the unannounced cessation of all service. Employees found their paychecks bouncing, and their jobs in limbo. CA&S had shut itself down without warning, citing it had no cash flow for operations and no funds to pay any outstanding debts.

A prime example of the ripple effect of the CA&S collapse occurred when neighboring regional Georgia Midland System (GAMS) found itself locked out of its primary interchange and lifeblood link with BNSF at Birmingham, AL. As with every other customer and business relation, the regional found only silence when it moved into normal weekend operations after that fateful Saturday. GAMS used CA&S trackage through Birmingham to reach BNSF’s East Thomas Yard from its main at Leeds, AL. After trying unsuccessfully that Saturday to contact CA&S officials, GAMS road forces literally commandeered the joint trackage and shared facility at the CA&S 32nd Street Yard in downtown Birmingham on September 3. Locks were cut, offices were forcibly opened and CA&S trains were re-routed over the GAMS or shoved into sidings as the GAMS worked to restore its connection and fluidity to the terminal operation.

By Wednesday, September 5, Federal officials moved in all over the CA&S system, confiscating records, sealing offices and officially closing down the railroad as the subject of a federal investigation into “questionable practices” by executive management. In Birmingham, GAMS managers and Federal officials played into a standoff, with threats of arrest and violence as GAMS refused to cease operations on the joint trackage and yard in Birmingham, AL. With the arrival of state and local law enforcement, GAMS officials and employees relented to the federal shutdown order and the terminal was idled again. GAMS trains and equipment were caught in the middle, as was every shipper and customer on the now defunct CA&S. The cat and mouse game with Federal officials continued into the next morning as GAMS tried to remove its trains and complete connections between its system and BNSF despite the lockdown of the former CA&S. Once again, GAMS crews cut locks and broke into offices in Birmingham in an effort to keep their own railroad from collapsing. A week after the abrupt shutdown, a federal bankruptcy judge officially took the CA&S into receivership. Federal investigators and GAMS officials hurled accusations at each other in the opening proceedings of the case, prompting the judge to grant the GAMS access to its interchange in Birmingham with the condition that it operate the CA&S as a court designated operator. GAMS guaranteed their interchange access to BNSF and saved their operation, but at the cost of running the whole CA&S estate. To make matters worse, the CA&S was a snarled mess of stranded trains, backlogged terminals and screaming customers. CA&S employees were either locked out or simply walked away, with no idea what would happen after the abrupt and very final shutdown of the railroad.

GAMS managers went to work with no hesitation, reeling from the shock of what they faced. Not only did GAMS managers have to restore normal operation to their existing system, but they had to create a workable operation for the defunct CA&S. Stop-gap measures were put into place on the CA&S and the railroad slowly lurched into operation by the weekend as GAMS pulled back in many of the CA&S displaced operations management and personnel. The restart created massive problems. GAMS found the CA&S system in a state of flux. Much of the core CA&S road power was out of service all over the system. In their place was dozens of short-term lease units with reliability marginally better than the units they replaced. Lessors of the units were screaming for the return of the units, or payment for time logged. Trains were stranded everywhere, terminals were clogged and no one seemed to know where anything was or where it was headed, since much of the computer management system had been seized as evidence in a federal investigation into management wrong doing. Damaged equipment from derailments and road failures related to lack of maintenance were scattered everywhere, clogging sidings and yards all over the system. New EMD units headed for delivery to the CA&S at the time of its collapse were stopped in Kansas City by EMD with orders not to deliver. These badly needed units were stored with orders to be returned to EMD. GAMS found that the CA&S had about half the fleet needed to run truncated train operations once lessor units where paid for or returned. After reporting its assessment of the CA&S to the bankruptcy court, GAMS immediately transferred every surplus working GAMS unit to the CA&S on a short-term lease in an effort to power trains stranded in yards waiting for locomotives. Operations and accounting records were returned, and for the first time in nearly two weeks, the CA&S had at least portions of data needed to restore some fluidity and get cars and shippers together.

The fact that CA&S had always been an exclusive EMD user created maintenance problems. GAMS was a solidly GE railroad and all the units transferred were GE built. Stephens Railcar was enlisted by the court to complete the outstanding CA&S projects, and charged with keeping the now mixed GE and EMD fleet serviceable on a minimum budget. With so work done for CA&S not paid, Stephens Railcar found itself indelibly tied to the fortunes of the imploded CA&S and its court appointed operator. With small security payments in hand from GAMS, Stephens Railcar set about the arduous task of rebuilding a fallen railroad’s roster.

Operations on the CA&S estate slowly moved to a strained routine by Christmas of 1996. GAMS and Stephens Railcar increased the pool of reliable second hand locomotives to the former CA&S fleet, sending the bulk of the rent-a-wreck lease units home for good. This freed up capital used to support these expensive leases for use in restoring and also maintaining the core CA&S fleet. GAMS found it had to move some intermodal trains to its own lines to meet contract requirements and quell penalty payments caused by the delays and failures surrounding the CA&S collapse and infrastructure deficiencies. Some track work was even addressed on the principal money-making routes in an effort to bring in needed revenue. Intermodal customers such as Evergreen Shipping gave the GAMS high marks and it appeared by January 1997 that the combined CA&S/GAMS operation was leveling out.

In January 1997, a consortium of on-line shippers and interested parties approached the bankruptcy judge with the idea of purchasing the CA&S. A principle backer was APL, who had formed the backbone of CA&S revenue. GAMS supported the measure also, noting that the strain of dual operation was starting to take its toll on GAMS resources. The judge agreed and on March 6, 1997, Gulf States Transportation assumed control and became the successor to the failed CA&S. Known shortly by its railroad name the Georgia Road, the new management tapped capital loans allowing it to begin a full rehabilitation of the former CA&S core network.

Georgia Road immediately took the reigns from GAMS, sending GAMS equipment back home where it was badly needed. To address red ink, Georgia Road began the process of rationalizing its railroad. Stephens Railcar was once again contracted as the primary heavy back shop, restoring guaranteed income to the rebuilding company in the form of new prepaid contracts. As part of payment for assumed CA&S debt, Georgia Road sent dozens of locomotives to Stephens Railcar, making the rebuilder an overnight owner of a large inventory of units ranging from newly rebuilt and operational to wrecked and retired. Most were stored in state around the system as Stephens Railcar mulled over what to do with its newly acquired locomotive fleet. Meanwhile, Georgia Road devised a smart new image that nodded to its heritage as the former Central of Georgia Railroad. Stephens Railcar set about plastering this new image on everything as the Georgia Road aggressively worked to erase all signs of the stigmatized CA&S.

In May 1997, the Georgia Road rerouted major traffic to what was considered its core system. Like the CA&S, the Georgia Road depended on intermodal as its primary income, but changes in the industry created a new environment. CA&S worked exclusively with UP as the APC contractor, using Midsouth as the link. When KCS purchased Midsouth in the late 1990s, the enmity between KCS and UP over the newly established Mexican Gateway ended the presence of APL trains on former Midsouth rails. Georgia Road had to re-established a connection with UP at Memphis, TN via trackage rights CA&S gained by not opposing the BNSF merger. CA&S was never needed to fully use these rights due to its Midsouth connection. Georgia Road inherited them along with the railroad and began using them in earnest in early 1998. APC stack trains and most manifests traded the water level Montgomery routing for the signalled ex-CofGA main between Birmingham and Macon. Out of Birmingham, Georgia Road ran the BNSF to Memphis for the direct connection with UP at via former MP lines in Memphis.

In June of that same year, Georgia Road sold most of it South Georgia and Central Alabama branch line traffic to the Alabama Midland RR, a start-up railroad purchased by the same Stephens family of Stephens Railcar fame. The former CA&S main from Meridian to Columbus went to the sale also, ending the line’s status as a Georgia Road main line intermodal route. AMRR picked up operations with little fanfare, utilizing many of the myriad of units returned to SRCS by Georgia Road. In July 1997, Georgia Road completed a second large sale transaction, paring all of its South Carolina trackage to GAMS. GAMS also acquired the Evergreen intermodal contract and the Sea-Path facility, which never progressed past Phase One plans. Also included was the Cedartown, GA to Griffin, GA line, and rights between Griffin and Columbus, GA as well as Griffin and Macon, GA.

Georgia Road not only succeeded in managing the former CA&S debt, but made money on the transactions. On January 1, 1998 it converted those gains into a purchase of the Florida East Coast Railway (FEC) from Port St. Joe Paper Corporation. The sale came as a complete surprise to the industry, notably NS who connected much of its Florida traffic to the FEC. NS was embroiled in a struggle with CSX over a potential Conrail takeover, and put up little resistance to the sale. FEC spent the mid 1990s struggling due to re-unionizing and a slumping Eastern Florida economy. Port. St. Joe divested the FEC as a way to raise capital to be used to support paper making operations, its core business.

Georgia Road quickly reorganized its holdings into two divisions. The FEC included the FEC railroad and all Jacksonville area operations, including the Jaxport port facility Georgia Road acquired just prior to the FEC transaction. All other lines were given to the Central Georgia Southern RR (CGS). Georgia Road became a holding company carrying all executive management, asset distribution, accounting, public relations and purchasing for all the owned railroads. The FEC proved a crux in Georgia Road operations, giving APL direct access into Florida all the way to Miami. Also, Florida shippers could now route goods all the way to UP in Memphis under one rate, which typically undercut both NS and CSX. The result was a gain in intermodal market share. Georgia Road was on the fast track, but determined not to self-destruct as its predecessor CA&S had a few years earlier. Test burns of Powder River Coal at various Southern Company electric generating plants also showed potential of sustained coal traffic.

Increasing delays on the over burdened BNSF trackage between Birmingham and Memphis created service breakdowns at times during 1998. Georgia Road worked various options with BNSF to improve operations, with only minimal results. Seeking a new route into Memphis, Georgia Road took an option from KCS to purchasing the former GM&O lines from Birmingham, AL to Fulton, KY via Artesia 1998. Upgrades to the lines allowed Georgia Road to get off the BNSF completely in 1999. Illinois Central RR (IC) completed the link to the UP by moving trains into Memphis from Fulton.

The “Artesia Secondary” lines purchased from KCS became the Alabama Interstate Railroad (ALIS). These lines made up the old Gulf & Mississippi regional that Midsouth swallowed in the late 1980s, running from Meridan, MS to Corinth, MS where it physically crossed the Fulton line. Along with the former Corinth and Counce Railroad operation, the Artesia Secondary included branches into Tuscaloosa, AL from Artesia, and Artesia to Newton, MS. Georgia Road managed to secure the CSX branch from Birmingham to Tuscaloosa, AL also, making a direct route from Fulton and the IC link into Memphis complete. Georgia Road also purchased more secondary trackage from NS in Alabama, gaining access to the port of Mobile and the heart of the Alabama paper and timber industry. Cancellation of trackage rights with BNSF created a net savings for the company, while garnering a solid overhead route between Memphis and the Deep South, with industry rich Birmingham, Alabama in the middle. Domestic and land bridge container and intermodal traffic once again polished the rails on the remnants of the old CA&S lines at levels never heard of at the height of CA&S operation.

While Georgia Road was busy building its Memphis-Florida Gateway, Canadian National RR tendered and offer to purchase and merge the IC. CN saw the IC as an answer to the denied CN-BNSF merger of 1999. Georgia Road immediately launched a campaign to stop the merger, even going so far as presenting a counter offer to buy the IC outright in what could easily be one of the premier railroad David and Goliath stories.. Georgia Road argued that the CN-IC merger would significantly adversely impact the Georgia Road by removing the IC as an independent partner. IC management was bent on selling out, realizing that the IC’s north-south orientation was detrimental in a day where East-West traffic was a must in order to survive. The resulting struggle raged through 2000 when both CN and Georgia Road realized that stock pricing driven up by their merger war would soon make any deals by either respective suitor excessively expensive.

Days before the Surface Transportation Board hearing on the matter, CN and Georgia Road inked an agreement that gave Georgia Road sole rights to the IC in exchange for granting CN open access to various major cities on the combined Georgia Road /Illinois Central system. Georgia Road officially became the principal stock holder of the IC on September 1, 2000 through a highly leveraged buyout of the IC. Six months later Georgia Road acquired the remaining stock in a buy-out/trade agreement and IC became a semi-autonomous affiliated railroad of the Georgia Road. The modern Georgia Road system was now a reality. Georgia Road could now connect the Deep South with every major Midwestern gateway city and the former Chicago Central trackage from Chicago to Council Bluffs brought the railroad within sight of the Powder River Coal Basin. Georgia Road could now control its own fate, working major interchanges directly without reliance on other Class One partners and their fickle agendas.

Georgia Road grew in size again in 2004 with the acquisition of the regional Georgia Midland System (GAMS). The privately held regional dropped into an abyss at the death of its owner, Wm. Wes Downs and Georgia Road could not afford to allow BNSF or CSX to gain control of the line that linked Birmingham with Atlanta and Charleston, SC. The very same lines sold off by the newborn Georgia Road in an effort to raise capital were now back in the corporate fold when Georgia Road exercised a first buy option forged between the GAMS and Georgia Road originally aimed at giving each partner the right to preserve connections in Birmingham. Few could have realized that is seemingly obscure option would become the linchpin to giving Georgia Road a sure footing in the rail transportation network in the Deep South. This time, however, Georgia Road had the means to capitalize on the direct routing to Atlanta and Charleston, allowing it to move key traffic off a circuitous route through Macon and Savannah, GA. Trains now headed due east from Birmingham over GAMS track that once was the western most arm of the Seaboard Airline Railroad directly into Atlanta, on the old Georgia Railorad to Augusta. At Augusta, traffic could move into Charleston via Greenwood. Trains headed to Florida could turn at Cedartown and bypass Macon’s former Brosnan Hump Yard, now also a Georgia Road facility. Georgia Road could now offer a dedicated third alternative for traffic moving into the growing Southeast, complete the land bridge of international container traffic moving from the West Coast to Eastern Seaboard, and tap into the growing industrial base on its core lines. The added benefit was the ability of Georgia Road to pare off certain lines of the original Georgia Road and Georgia Midland System to help pay for upgrades to the new system. These lines were picked up by the Alabama Midland Railroad, widening its traffic base.

The year 2004 was also notable in Georgia Road’s full implementation of the “Quicksilver Intermodal Service” (QSI). This new brand name embraced the general long distance intermodal operations other than those of the Eagle Flyer Service. A push to gain medium and short haul intermodal for LTL truckers such as USPS, UPS, ABF, Roadway and FedEx Freight also started as Georgia Road opened Regional Intermodal Service Centers (RISC) at strategic points between interstate corridors to provide a fast and cost effective rail vs. highway option. This Quicksilver operation was called the “Quicksilver Optima” service and employed the use of freely mixed traditional intermodal, all purpose well cars and roadrailers in Optima, or”optimized scheduled” trains. With its GAMS purchase, QuickSilver Intermodal could now boast terminals all over the Eastern Seaboard and Midwest.

As Georgia Road moved through the mid 2000s, it watched with great interest how KCS had built up its Meridian Gateway and used trackage rights and newly acquired dormant lines to acquire the TFM railroad in Mexico. The Mexican government saw the privatization of its NdeM, a major hurtle in utilizing the NAFTA free trade agreement negotiated in the Clinton presidency years. KCS beat out UP as the suitor for the TFM, and UP set out to shore up the Ferromex side of the new private Mexican railroad system. Georgia Road stepped in an negotiated it own agreement with Ferromex, under its new MexXpress service, using a combination of Georgia Road, UP and BNSF trackage rights garnered by not opposing the UP-SP and BN-ATSF mergers. As KCS looked for capital to rebuild its Meridian Gateway to allow for it to competitively to compete with BNSF and UP into the Southeast, Georgia Road signed a joint agreement with KCS to help fund a massive upgrade to the line from Shreveport, LA to Dallas, TX. In return, KCS granted overhead rights into Dallas. Georgia Road then acquired the Fort Worth & Western RR (FWWR) and various dormant Texas state-owned and dormant traffic to connect physically with Ferromex at Presidio, TX. In 2007, Ferromex-Georgia Road intermodal trains began running the dedicated route from the border into the now major classification point at Birmingham, AL in the new Dale Classification Yard and Lareda Inland Containerport.

As the recession of 2009 loomed in late 2008, Georgia Road announced its intent to acquire the DME-ICE regional in the Central Northwestern US. The regional had just managed to secure all the permits to built it own line into the Powder River Coal Basin at Bill, Wyoming, but lost FRA loans needed to actually start the construction. Georgia Road purchased the railroad as its DME subsidiary, and pulled from its substantially larger coffers money and loans to complete the link into the coal region by early 2010. With this link in place, Georgia Road could now effectively

control all Powder River Coal coming in and out of generators in the Southeast, amounting to some three dozen trains per week, more than doubling a large portion of its revenue breakout.

In an effort to continue to broaden its traffic base, Georgia Road implemented its first Regional Automotive Service Center (RASC) in the Bessemer suburb of Birmingham, AL. This concept linked the idea of a regional fast on-fast off RISC setting programmed to serve the increasing number of foreign automakers in Georgia, Alabama and Mississippi. Mercedes sat on one side of greater Birmingham, and Honda on the other. Not only did they need “just in time” delivery of parts to supplies brought in from the ports on containers, but their various product lines had to be sorted and forwarded to markets over North America. Unlike US automakers, who typically specialized each facility to a limited make or model, these foreign makers used flex assembly lines capable of producing defined lots of many models with minimal change-over and no retooling. Once more, favorable dollar values abroad encouraged these makers to include more of the process inside the United States to control costs and eliminate losses due to currency fluctuation caused by the world-wide recession. Mercedes was the first to move more operations to its Vance, AL plant, linking suppliers in Germany to the plant via port facilities at Savannah, Brunswick and finally the underutilized Sea-Path in Charleston. The Warrior RASC in Bessemer proved the concept, as Mercedes initiated container trains from eastern ports rolled in for unloading and forwarding to its Alabama assembly plant and its suppliers. Honda quickly joined up, effectively doubling capacity and requiring Georgia Road to open its new Leigh Yard to handle these specifically defined and time sensitive operations. Using its QuickSilver links through the AMRR-FGC system, the foreign automotive business increased again as Georgia Road linked its own network RASC and RISC facilities with those of KIA, Hyundai, Honda, Toyota, Mercedes and VW .

As the first decade draws to a close, Georgia Road continues to prove that old dogs can not only learn new tricks, but that these tricks are something no always seen before. Where CA&S burned itself out too quickly trying to maintain its reputation as the “prima-donna railroad of the 1990s, Georgia Road has show a more studied approach with a keen interest in customer service will support sustained growth, even in economic turmoil. The railroad continues to position itself for growth in a down market, placing all its efforts under the same “Driven to Service” slogan that donned the first fully painted Georgia Road locomotive twelve years ago.

END OF LINE

|

|